Ice Houses, Before the Freezer: How Underground Domes Kept Summer Cool

Discover the history of ice houses—underground domes insulated with straw that stored winter ice through summer, long before freezers and fridges.

FOOD HISTORY & TRADITIONS

Before freezers and fridges became household staples, keeping food and drinks cold required creativity—and a surprising amount of engineering. For centuries, the answer lay underground, in the form of ice houses: specially built structures designed to store ice harvested in winter and keep it frozen through the hottest summer months.

From the 17th century through the early 20th, these domed chambers—lined with straw and stone—were the backbone of cooling for estates, cities, and even international trade. They weren’t just functional; they were feats of ingenuity, able to preserve ice for months, sometimes even until the following winter.

How Ice Houses Worked

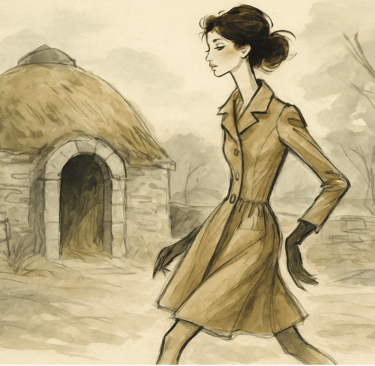

At their core, ice houses were insulated vaults, often dug deep into the earth where temperatures stayed naturally cooler. Most took the form of rounded or conical domes, with thick brick or stone walls and a thatched or soil-covered roof to buffer against the sun.

Inside, workers stacked blocks of ice—harvested during the depths of winter from lakes and rivers—into tightly packed mounds. To prevent melting, they filled gaps with insulating materials like straw, sawdust, or peat, creating a buffer layer that trapped cold air and absorbed excess moisture. Some ice houses included drainage channels to carry away meltwater, preventing it from accelerating the thaw.

A well-constructed ice house could hold thousands of pounds of ice, keeping it frozen not just through summer, but in some cases for an entire year. Access was usually through a narrow, shaded passageway, allowing workers to retrieve ice without flooding the interior with warm air.

The Winter Harvest: How Ice Was Stockpiled

Stocking an ice house was no easy feat. Each winter, once lakes and rivers froze solid, crews would saw and chisel enormous blocks of ice from the surface. These blocks—sometimes weighing hundreds of pounds each—were hauled by horse-drawn sleds or wagons to the estate or town ice house.

The process was labor-intensive and often dangerous. Workers spent long hours on frozen water, guiding the horses, hauling the ice, and cutting neat, geometric grids to make the blocks easier to transport. Once the ice reached the storage vault, it had to be carefully stacked, with insulating layers added between each row.

But the effort paid off. Come July, that frozen bounty meant cool drinks, fresh meat, and even early ice creams for those with access. For estates and wealthy households, it became a mark of refinement to offer chilled wine or sorbet at the height of summer—luxuries that were impossible without a well-stocked ice house.

Symbols of Status and Survival

Ice houses weren’t just practical. They were symbols of wealth and sophistication, especially across Europe and North America in the 18th and 19th centuries. Aristocrats and landowners built ornate ice houses on their estates, some designed to look like classical temples or decorative follies, turning a utilitarian structure into a display of status.

For urban areas, ice houses were critical to trade and public health. Stored ice supplied markets, breweries, hospitals, and households, keeping perishable foods safe and allowing cities to function during sweltering summers. Some merchants even turned ice storage into a booming business, exporting blocks of frozen water to warmer regions. In the 19th century, New England ice was shipped as far as the Caribbean, India, and South America, making “cold” a global commodity long before the advent of electricity.

Fun Fact: Year-Long Ice

The best-built ice houses could preserve ice for a full twelve months, allowing a block harvested in January to last until the next winter’s harvest. A few estates kept such surplus ice that they not only met their own needs but also sold or exported it, proving that ice was as much a luxury as it was a necessity.

The Decline—and Survival—of Ice Houses

With the arrival of mechanical refrigeration in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, ice houses began to fade from daily use. By the 1920s, electric freezers and refrigerators were becoming more common in cities, and commercial refrigeration took over the work of storing and shipping ice.

Many ice houses were abandoned, collapsing back into the earth or converted into storage spaces, wine cellars, or even tourist attractions. Yet hundreds still survive across Europe and North America, some preserved as heritage sites. Visiting one today offers a glimpse into a world where staying cool took planning, manpower, and ingenuity—a stark contrast to the ease of opening a fridge door.

Why Ice Houses Still Fascinate

Ice houses tell a story not just of technology, but of culture. They reflect a time when cold itself was a luxury, something that required labor, coordination, and careful architecture to secure. They also highlight the creativity of pre-electric societies, who mastered natural insulation and clever engineering to solve problems we now take for granted.

In a world grappling with sustainability and energy concerns, these historic vaults even hold lessons for the future. Their ability to maintain cold temperatures without machinery has inspired modern architects and environmental engineers looking for low-energy cooling solutions.

So, the next time you sip an iced drink in July, spare a thought for the ice houses—those quiet, domed chambers tucked beneath estates and farms—that once made summer bearable, one block of winter’s bounty at a time.