The First Picnic Wasn’t What You Think: From French Salons to Fields

The first picnic wasn’t outdoors. Discover how the 18th-century French pique-nique began as an indoor feast of shared food before evolving into the blanket-and-basket ritual we know today.

FOOD HISTORY & TRADITIONS

When we hear the word picnic, we think of sunny fields, wicker baskets, and gingham blankets spread across green grass. It feels timeless, a celebration of leisure and nature. But the original pique-nique—as the French first called it—looked nothing like our modern version. In fact, it didn’t even take place outdoors.

The first “picnics” of the early 18th century were indoor social feasts, where well-to-do friends gathered in salons or drawing rooms, contributing whatever food and drink they could bring—often leftovers—to create a communal, mismatched spread. What we now think of as a rustic outdoor ritual began as something far more urbane, a response to the rigid dining customs of the time.

Paris, 1700s: The Birth of the Pique-Nique

The word pique-nique first appeared in French writings in the late 17th century and gained popularity in the 18th. It combined piquer, meaning “to pick,” with nique, a colloquial term for “a small thing.” Together, the phrase described the act of “picking at little things”—grazing, sampling, and sharing rather than sitting down for a structured, multi-course meal.

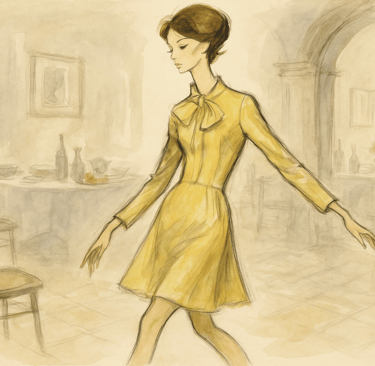

These early picnics were the invention of the fashionable elite. Parisian salons hosted the gatherings, where guests in silk and lace arrived with wine, pastries, meats, cheeses, or fruit. The charm of a pique-nique was its informality compared to formal dining, which at the time was governed by strict etiquette, hierarchies, and carefully orchestrated service.

Here, instead, guests might lean back on couches, laugh freely, and help themselves to whatever dish caught their eye. It was convivial, improvised, and social—a setting where conversation and camaraderie mattered as much as the food itself.

From Salons to the English Countryside

The pique-nique made its way to England in the late 18th century, brought by French émigrés and Anglophiles fascinated with continental trends. But the British, with their growing Romantic fascination with nature, soon reimagined it. By the early 1800s, “picnics” in England often moved outdoors, into manicured gardens, estates, and eventually open fields.

These weren’t yet the casual blanket picnics we know. Early English picnics could be extravagant affairs, hosted by exclusive “picnic societies” and attended by the upper classes. Some included live music, theatrical performances, and formal entertainment, making them more like roving private banquets than relaxed meals.

Still, the shift outdoors reflected a broader cultural moment. The Romantic era encouraged people to seek beauty and inspiration in landscapes, treating the countryside not just as a resource but as a setting for leisure and reflection. Eating al fresco became a fashionable way to immerse oneself in that ideal.

The Picnic We Know Today

It wasn’t until the 19th and early 20th centuries that the picnic evolved into the form familiar today: a casual, portable meal shared in a park or countryside, often spread on a blanket, with simple foods packed into baskets. The Industrial Revolution, growing public parks, and the rise of middle-class leisure all contributed to its democratisation.

What began as a symbol of elite sociability became a family and community tradition. By the Victorian era, illustrated magazines were publishing idealised scenes of families enjoying picnics by rivers and in meadows. Portable food like sandwiches, pies, and bottled drinks made the outing practical, while inexpensive blankets and baskets became widely available.

By the early 20th century, the picnic had fully transformed from the pique-nique’s silk-and-salon origins into a more rustic, accessible custom—though one still tied to a sense of occasion and escape from the indoors.

Fun Fact: The Picnic Societies

The first English “picnic societies,” formed in the early 1800s, were surprisingly lavish. Members pooled resources to fund musicians, performers, and large quantities of food and drink, turning their “picnics” into semi-private festivals. Far from a humble affair, these gatherings often cost more than formal dinners, proving that the picnic’s journey to the casual, accessible outing we know today was anything but straightforward.

Why the Picnic’s Origins Still Surprise Us

The history of the picnic reveals how cultural trends reshape even the simplest traditions. What started as an indoor, urban gathering for the elite gradually morphed into an outdoor ritual enjoyed by all. The shift wasn’t just about location; it reflected changing ideas about leisure, nature, and sociability.

The next time you pack a basket and head for a sunny field, picture its earliest incarnation: a candlelit room in Paris, laughter echoing through a salon, and friends in embroidered waistcoats and gowns grazing on shared delicacies. Our picnics may feel timeless, but they carry a story that began far from the meadow.