The Healer, the Cook, the Witch

Many women accused of witchcraft were simply skilled in healing and cooking. Explore the blurred line between healer, cook, and witch — and their powerful legacy.

WITCHY KITCHEN

Three roles in one — and all threatened by fear

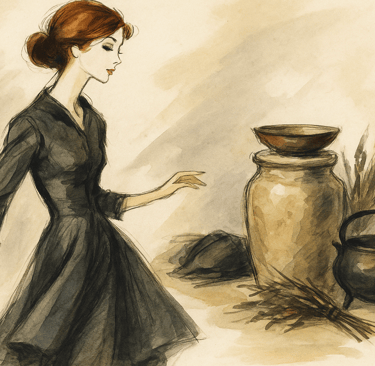

She stood at the hearth — a pot simmering, herbs drying above her, a child coughing in the next room. She might have been called mother, midwife, healer — or, if the neighbours were afraid, something darker: witch.

Throughout history, in rural kitchens and herbal gardens across Europe, the roles of healer, cook, and witch were often one and the same. And for many women, this knowledge — powerful but unwritten — became both a source of survival and a reason for suspicion.

Women’s Knowledge: Revered, Feared, and Unwritten

In pre-modern villages, the most essential forms of care weren’t taught in universities. They lived in the hands of women. These were women who:

Knew how to preserve a cabbage before winter

Could break a fever with elderflower and vinegar

Understood which roots to steep in wine to help a sleepless child

Knew which mushrooms not to eat — and which could cure infection

This was not mystical knowledge. It was practical, ancestral survival. But it was rarely written down. It passed from woman to woman, whispered at night, practiced by firelight. And because it lived outside the male-dominated structures of church, state, and medicine — it was easily weaponised.

The Thin Line Between Healer and Witch

A woman who used plants to ease pain was useful — until something went wrong. If a child died of fever, if the crops failed, or if a neighbour fell ill, her invisible knowledge became dangerous. Suspicion crept in:

Was the broth really healing?

Did the mint tea hide a curse?

Why does her food smell too sweet?

In medieval Europe, many of the women burned, drowned, or hanged as witches were herbalists, midwives, or food preservers. They were healers of the poor, keepers of seeds, and the only “doctors” in walking distance.

Their kitchens weren’t restaurants — they were medicine cabinets, ritual spaces, and command centres.

When the Kitchen Was Power

Cooking wasn’t just a chore — it was alchemy. The kitchen was where women blended flavours, fought illness, managed scarcity, and marked the seasons.

The healer used wild herbs and garlic under beds during plague

The cook fed communities through famine with foraged greens and pickled roots

The witch — or the woman accused of being one — was often just too skilled, too independent, or too vocal

These women owned no land. They had no titles. But they held knowledge. And that was enough to make them dangerous.

A Legacy Still Overlooked

Today, we no longer drown women for knowing how to cure a headache — but the legacy lingers.

Women’s food knowledge is often dismissed as “intuitive” or “old wives’ tales”

Culinary skills passed down through generations are rarely seen as scientific

Herbal knowledge is marketed now — but stripped of the credit due to those who protected it for centuries

And yet, every time you simmer onions for someone who’s ill, you echo the healer.

Every time you write down a recipe or dry herbs, you honour the witch.

Every time you cook with love and intention, you embody all three.

Fun Fact

In 15th-century Germany, several women were accused of witchcraft for serving food that “smelled too sweet” or made men “desire sleep.” The so-called spells? Likely gentle herbal sedatives — calming teas made with chamomile, lemon balm, or valerian. Remedies long used by village women and now sold in health shops worldwide.