The Secret Grief of the Summer Kitchen: Women, Canning, and the Weight of Invisible Labour

Explore the hidden emotional toll of the summer kitchen, where women endured isolating, exhausting canning work in the 19th and early 20th centuries.

FOOD HISTORY & TRADITIONS

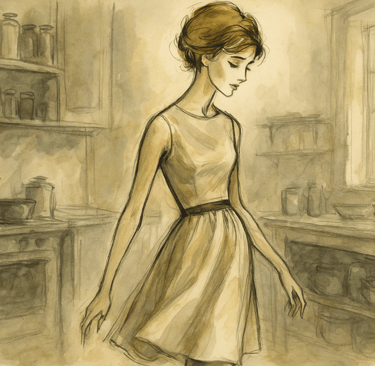

In the sweltering heat of midsummer, when fields hummed with cicadas and the brief northern summer seemed to brim with life, another scene unfolded behind closed doors. In farmhouses and rural homes across Europe and North America during the 19th and early 20th centuries, women stood in kitchens so hot they felt like furnaces.

It was canning season—a relentless stretch of weeks spent peeling, boiling, stirring, and sealing, all to capture the fleeting abundance of summer in jars. To outsiders, it might have looked like quaint domesticity, a homely ritual of jam-making and pickle-packing. But for the women who lived it, the summer kitchen was a place of isolation, exhaustion, and often unspoken grief—labour so demanding and yet so expected that it rarely earned acknowledgment, let alone praise.

The Reality of the Summer Kitchen

Diaries, letters, and oral histories from women of the era paint a stark picture. Canning and preserving weren’t leisurely pursuits; they were survival work, crucial to ensuring a family had enough food through autumn and winter. During the high season, some women processed hundreds of jars in a matter of weeks: tomatoes, peaches, cucumbers, jams, chutneys, and relishes—all bubbling in vats of sugar, vinegar, and brine.

The conditions were punishing. Kitchens, already stifling in summer, became ovens as kettles boiled for ten or twelve hours a day. The air grew thick with steam and sticky with sugar. The work was repetitive and physically taxing: scalding jars, peeling endless piles of produce, stirring heavy pots, and lifting sealed jars onto shelves.

And there was no respite. This was not a hobby or seasonal treat; it was a duty. A failed batch could mean less food for the winter, an added burden on already precarious households. Success was expected. Failure could bring shame.

The Invisible Weight of Domestic Labour

What stung most for many women wasn’t just the labour—it was the invisibility of it. While the preserved food was celebrated at winter meals, the sheer volume of work that went into those gleaming jars was rarely acknowledged. Canning was categorised as “women’s work,” something done as naturally and unquestioningly as washing or mending, and therefore undeserving of praise.

Some women expressed this frustration openly in journals, describing the loneliness of the summer kitchen. While men and older children worked outdoors, harvesting or repairing, and younger children played in the rare sunshine, women were confined to their boiling, steamy domain. The constant hiss of kettles and the rhythmic pop of sealing jars replaced conversation.

This emotional weight is clear in surviving accounts. One Midwestern farm wife wrote in 1910: “I have sealed 180 jars since Monday. My hands ache, and the house is a sauna. They will enjoy the fruit in January, but no one will think of this week. I feel as if I might dissolve into the steam myself.”

Finding Relief in “Canning Clubs”

Out of this isolation, some women found a way to turn the work into something bearable—even communal. By the late 19th century, informal canning clubs began to emerge in rural communities. These were not official organisations but loose gatherings of neighbours, friends, and relatives who rotated kitchens, sharing the labour and the company.

Canning clubs were often more about companionship than efficiency. Women would divide tasks—one peeling, another stirring, another sterilising jars—while trading stories, gossip, and advice. The work still got done, but the burden felt lighter when carried together.

In some areas, these gatherings became semi-formal events, with women scheduling their preserving days to align. While the clubs didn’t erase the exhausting nature of the labour, they gave women a chance to connect, to vent, and to transform the summer kitchen from a site of solitary toil into a place of shared resilience.

Fun Fact: Summer Kitchens as Survival Spaces

Many farmsteads built separate summer kitchens—detached or semi-detached buildings used exclusively for canning and preserving. This wasn’t just practical for ventilation; it allowed families to keep the main house cooler during scorching weather. Some of these summer kitchens, now preserved as historical sites, reveal how seriously the task was taken: massive wood-burning stoves, long counters, and rows of shelving built purely for preserving work.

Even with these dedicated spaces, the labour was grueling. Women might spend entire weeks in these buildings, rarely stepping outside except to fetch water or wood. For some, the isolation of the separate kitchen deepened the emotional toll, while for others, it offered a strange kind of reprieve from the crowded main house.

Why This Story Still Resonates

The grief of the summer kitchen speaks to a broader truth about women’s domestic labour, past and present. So much of it has been invisible, framed as obligation rather than work, and stripped of recognition despite its vital role in family survival.

Today, canning has become a hobby for many—a craft revived by homesteaders, food enthusiasts, and sustainability advocates. For those who choose it, the process can feel meditative or even empowering. But the historical context lingers. For generations of women, preserving food wasn’t a choice; it was a seasonal gauntlet, endured in silence.

Remembering this history adds weight to every jar we open today. It reminds us that the glistening preserves on the shelf represent not just fruit and vinegar, but hours of unseen labour—hands scalded, backs aching, and women who often felt themselves disappearing into the very steam that sustained their families.