The Strawberry Craze of Tudor Courts: How Henry VIII Turned a Summer Fruit into a Royal Symbol

Discover the strawberry craze of Tudor England, from Henry VIII’s love of strawberries and borage to their symbolism of love, fertility, and luxury at Hampton Court.

FOOD HISTORY & TRADITIONS

In the dazzling world of Tudor England, food was never simply sustenance. It was theatre, wealth, and symbolism rolled into one—every dish designed to impress as much as to feed. Among the roasted boar, towering sugar sculptures, and honeyed pies that lined the banquet tables of Hampton Court, one seasonal treat stood apart as both a delicacy and a statement: the strawberry.

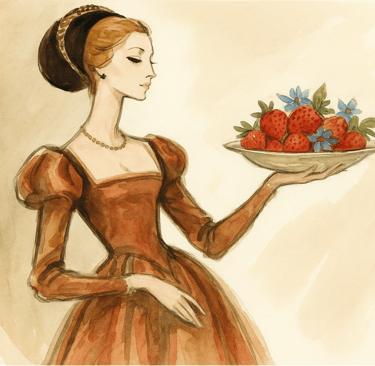

To us, strawberries might seem ordinary—a sweet summer fruit. But to Henry VIII and his glittering court, a bowl of ripe, ruby-red berries, scattered with delicate blue borage flowers, was far more than dessert. It was a symbol of vitality, love, and power, a flourish designed to dazzle, seduce, and speak volumes without a single word.

A Banquet Spectacle at Hampton Court

Picture the great hall at Hampton Court on a warm June evening. The walls are hung with rich tapestries, the air alive with the mingling scents of roasted venison, spiced pies, and freshly cut herbs. Courtiers in their finest silks and brocade cluster around long, candlelit tables, laughing over silver goblets of wine and ale as musicians play above in the gallery.

And then, amid the spectacle of golden platters and steaming dishes, a quieter but no less striking presentation arrives: bowls of freshly picked strawberries, glistening like rubies, their deep red softened by a scattering of delicate, star-shaped borage blossoms.

This was no casual garnish. In an age when sugar was a rare and expensive luxury, and fresh fruit was a privilege reserved almost exclusively for the wealthy, the arrival of strawberries was an event in itself. Their fleeting growing season made them precious, their beauty and flavour irresistible. To serve them was to transform a lavish meal into an unforgettable performance, one that hinted at romance, vitality, and the fleeting sweetness of summer.

More Than a Dessert: A Symbol of Love, Power, and Desire

The Tudors spoke a language of food, and every dish carried meaning. A roasted peacock in full plumage might declare status; a sugar sculpture could announce wealth and mastery over distant trade networks. But strawberries whispered of something softer and more intimate—pleasure, life, and the ever-pressing themes of love and fertility.

Their symbolism was widely understood. The strawberry’s vivid, heart-red hue linked it to vitality and romance, while its shape and flavour lent it an air of sensuality. Paired with borage, whose starry blue flowers were believed to “cheer the heart” and stir courage in men and passion in lovers, the combination took on a near-magical allure. For Henry VIII, whose hunger for both feasting and heirs was infamous, such symbolism was intentional. The king was known to favour this pairing at his banquets, offering it as much for its beauty and taste as for the messages it carried about abundance, potency, and pleasure.

Beyond its connotations, the strawberry was also a status symbol. Few outside the nobility ever tasted one fresh, and those who did often encountered it sweetened with imported sugar—a substance so costly it was locked away in chests and used sparingly even by the elite. A dish of strawberries dusted with sugar was more than dessert; it was a display of wealth and global reach, proof that the host had access to the rarest luxuries of the age.

Tudor Alchemy: Strawberries as Potions and Pleasures

The strawberry craze didn’t stop at the banquet table. Tudor cooks and brewers found other ways to weave the fruit into their repertoire, often in ways that blurred the line between food and medicine—or even food and magic. One particularly popular indulgence involved sugaring strawberries and floating them in wine, ale, or a sweet herbal syrup, creating a drink that was both refreshing and suggestive.

Herbalists of the era claimed such mixtures could “cheer the heart,” lift the spirits, and encourage affection, particularly when paired with herbs like rosemary or mint. In a courtly setting, sharing such a drink with a lover or would-be suitor carried a hint of charm and flirtation, a socially acceptable nod to desires that were otherwise carefully veiled. Some even whispered that these concoctions worked as a kind of Tudor love potion, turning a simple fruit into a key player in the court’s quiet games of romance and intrigue.

In this way, strawberries became more than just a fleeting summer luxury; they became a tool of mood, message, and manipulation, a way for hosts and lovers alike to infuse their tables with meaning as well as flavour.

Why the Tudor Strawberry Legacy Endures

Henry VIII’s fascination with strawberries reflects more than his personal tastes. It illustrates the Tudor approach to dining as spectacle, where every bite told a story and every banquet was as much about power and performance as it was about satisfaction. A gilded sugar castle might wow the crowd, but a bowl of berries—red, fresh, and fleeting—offered something more visceral: the immediacy of pleasure, the suggestion of vitality, and a sweetness that lingered long after the feast ended.

That association has endured. Today, when we spoon strawberries into cream at Wimbledon, sip a glass of champagne garnished with a berry, or serve them as the crowning jewel of a summer dessert, we are unknowingly echoing a tradition that began centuries ago. To the Tudors, strawberries were luxury, celebration, and love—all captured in a single, ephemeral bite.

So the next time you taste a strawberry, imagine the glow of candlelight on Hampton Court’s towering walls, the hum of music and laughter, and a king—England’s most notorious showman—raising a bowl of berries and borage to his courtiers, offering in that one gesture a toast to life, love, and the enduring power of food to speak without words.