The Wild History of Gin & Tonic: From Malaria Medicine to Cocktail Classic

The gin and tonic began as a malaria cure, not a cocktail. Discover how British officers in India mixed quinine tonic with gin to survive—and created a classic.

FOOD HISTORY & TRADITIONS

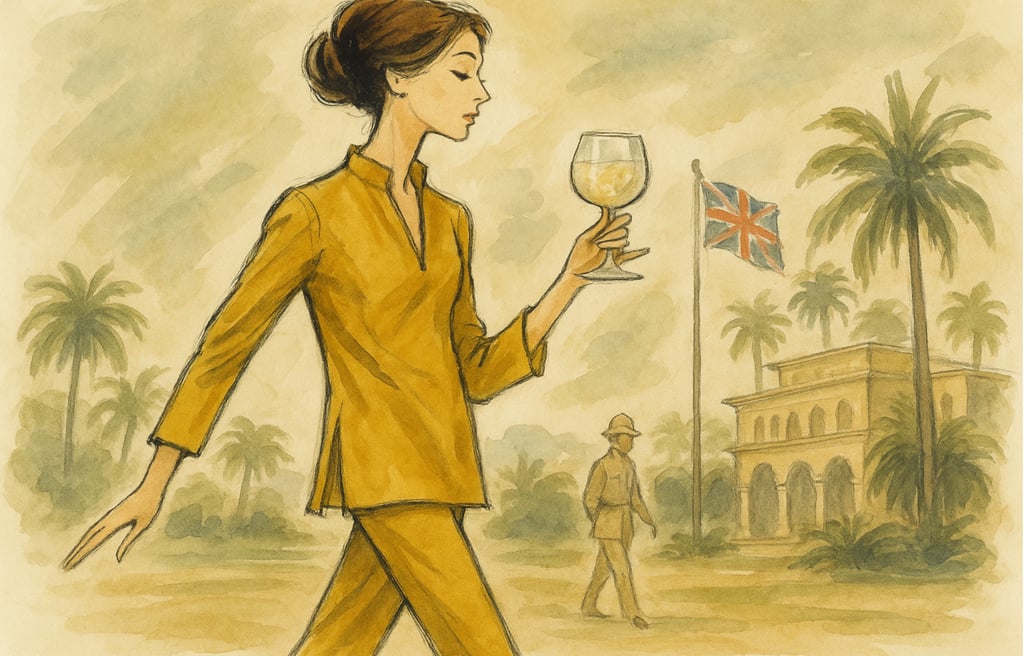

On a warm evening, a gin and tonic feels like the epitome of sophistication—crisp, refreshing, and perfectly suited to slow sips under fading sunlight. But behind its elegance lies a far rougher origin story. This classic drink, now a bar staple, was born out of necessity, medicine, and empire, not cocktail culture.

In the 19th century, British officers stationed in malaria-ridden regions like India weren’t searching for a new happy hour beverage. They were trying to survive. And the gin and tonic, long before it was a fashionable drink, was a life-saving concoction built around a bitter, bark-derived medicine called quinine.

Quinine: Bitter Lifesaver of the Empire

Malaria was one of the most serious threats to colonial armies and administrators. The fever could devastate entire garrisons, and without treatment, it was often fatal. The only known preventative was quinine, an alkaloid extracted from the bark of the cinchona tree, native to South America.

By the 18th century, quinine had been adopted across Europe as both a treatment and a prophylactic. It worked—but at a cost. Dissolved in water, quinine created a “tonic” so bitter and astringent that few could stomach it. Soldiers were expected to consume it daily, but compliance was poor; no one wanted to swallow a liquid that tasted like punishment.

To fix the problem, British officers stationed in India began experimenting. They added sugar and lime to soften the taste, and most importantly, mixed it with gin, the spirit they already had in ample supply. The botanicals in gin—juniper, coriander, citrus peel—masked the worst of the quinine’s bitterness, turning medicine into something almost enjoyable.

The Birth of a Colonial Ritual

What began as a forced daily dose soon became a ritual. By the early 19th century, the gin and tonic was part of the colonial officer’s routine, consumed at sunset as both a malaria preventative and a social custom.

The drink became deeply tied to the rhythms of life in the Raj. Officers and their families gathered on shaded verandas, sipping gin and tonics while the day’s heat faded. The addition of lime juice not only improved the flavour but also provided a dose of vitamin C, helping ward off scurvy on long postings.

In time, the quinine content in tonic water was standardised and sweetened, making it less medicinal and more palatable. By the late 1800s, commercial tonic waters like Schweppes were being bottled and shipped globally, and the gin and tonic was on its way to becoming a global beverage, not just a colonial survival tool.

From Lifesaver to Leisure

By the 20th century, medical advances and changing tastes meant the gin and tonic’s role as a literal lifesaver faded. Quinine levels in commercial tonic dropped dramatically—today’s tonic water contains only a fraction of the original amount, far too little to offer malaria protection.

But by then, the drink had transcended its origins. Its crisp, slightly bitter profile appealed to drinkers well beyond the colonies, and by the 1920s and 30s, it had cemented itself as a cocktail bar standard from London to New York.

The gin and tonic also benefitted from the evolving gin industry itself. London dry gins, with their cleaner, crisper profiles, paired beautifully with tonic, while regional variations (from Dutch genever to modern craft gins) gave the drink endless room for reinvention.

Today, far removed from the jungles of India, the gin and tonic is a symbol of leisure rather than necessity—a testament to how a drink born from survival can transform into an enduring icon of refreshment.

Fun Fact: The Glow of Quinine

Even in its modern, mostly decorative form, quinine retains one of its original quirks: it glows under ultraviolet light.The natural fluorescence of quinine means that your gin and tonic can literally light up under blacklight—a lingering trace of the drink’s medicinal, slightly otherworldly origins.

Why Its Origins Still Matter

The gin and tonic’s colonial roots are a reminder that some of our favourite modern comforts have surprisingly rough beginnings. What we now associate with summer terraces and craft cocktail menus was once a daily necessity for survival against one of humanity’s deadliest diseases.

Its evolution also reflects the broader story of the 19th and 20th centuries: the spread of global trade, the fusion of European and local practices, and the way necessity often births enduring traditions.

So the next time you raise a glass, consider that your drink—bubbly, crisp, and refreshing—once helped British officers endure sweltering outposts and lethal fevers. It’s not just a cocktail. It’s history in a glass.