Why Barbecuing Is So Gendered: The Mid-Century Marketing Trick That Stuck

Discover how mid-century marketing made barbecuing a “man’s domain,” turning grilling into a symbol of masculinity while women did the behind-the-scenes work.

FOOD HISTORY & TRADITIONS

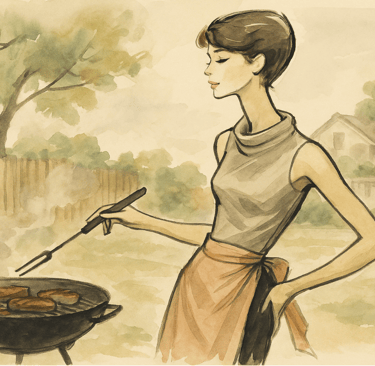

Picture a sunny backyard in the 1950s. A father stands by a gleaming charcoal grill, spatula in hand, wearing a jaunty apron that declares him “King of the Coals.” His wife, dressed neatly in a summer dress, lays out bowls of potato salad and condiments on a picnic table. The children hover nearby, waiting for the burgers and steaks sizzling over the flames.

It’s a familiar image, one we still see echoed in advertisements, movies, and even our own backyards. But how did grilling—simply cooking outdoors—become so strongly coded as a masculine activity, while indoor cooking was framed as women’s work? The answer isn’t tradition or instinct. It’s marketing. And it began in mid-century America.

How Marketers Turned the Grill into a “Man’s Space”

In the decades after World War II, American companies were looking for ways to sell a new wave of consumer goods to a growing middle class. Barbecue grills, charcoal, and meat products were booming, but advertisers faced a cultural challenge: cooking had long been viewed as a woman’s domain, a chore tied to the drudgery of the kitchen.

To make barbecuing appealing to men, marketers reframed it completely. Adverts and magazines began portraying grilling as the opposite of domestic work—not drudgery, but escape. Men weren’t cooking; they were “mastering fire,” communing with the outdoors, and taking part in a primal ritual that echoed the hunter-gatherer past.

Grilling was cast as a weekend reprieve from the office and from the feminised space of the kitchen. Unlike baking a pie or boiling vegetables indoors, flipping steaks over open flames was presented as rugged, adventurous, and even heroic. One ad from the era proclaimed, “The boss of the pit—bringing man’s fire to the family table.”

Women Prepped, Men Performed

This gendered framing didn’t erase women’s role in mealtime—it just repositioned it. While men were pictured as the stars of the barbecue, their contribution was largely ceremonial. Wives typically did the bulk of the actual work: seasoning and marinating the meat, preparing side dishes, setting up the table, and cleaning up afterwards.

The husband’s job was to appear at the grill for the moment of drama—the sizzling, the smoke, the carving—and then bask in the praise as the “grill master.” Advertisements leaned into this division, often joking that grilling was simple enough that even men, “unaccustomed to kitchen work,” could do it.

It was a clever balancing act. Men got a taste of culinary control without threatening the cultural expectation that the household kitchen remained a woman’s space. Women, meanwhile, were expected to handle the less glamorous parts of the meal while smiling approvingly at their husband’s brief display of “caveman spirit.”

The Caveman and the Sales Pitch

Many mid-century ads outright leaned into the idea that barbecuing was a man’s return to primal instincts. Slogans like “Rule your fire” and “Every man a caveman” cast grilling as something elemental and instinctive, appealing to a post-war generation eager to embrace both domestic comfort and a sense of rugged masculinity.

The result was a powerful marketing narrative: grilling wasn’t just about food; it was about identity. Owning a grill became a symbol of prosperity, masculinity, and suburban stability. Companies sold not just equipment and meat, but a vision of the “ideal” American family, with father at the helm of the flames and mother curating everything else.

This image proved so sticky that it has persisted long after the cultural forces that created it faded. Even today, barbecue brands and television ads often depict men as the masters of the grill, while women are shown preparing salads or desserts. The roles may have softened, but the echoes of 1950s marketing still shape how we picture a cookout.

Fun Fact: From Ads to Aprons

Some of the most iconic mid-century barbecue ads featured humour aimed at men’s supposed lack of kitchen skills. One campaign for a popular grill brand promised that “even a man” could handle the job because barbecuing required “no pots, no pans, no measuring—just meat and fire.” Another dubbed the male cook “The Backyard King,” encouraging sales of branded aprons, tools, and beer coolers that made grilling a full-blown ritual.

These ad campaigns did more than sell products. They entrenched the notion that outdoor cooking was masculine not because of history, but because it was profitable.

Why the Gender Coding Still Lingers

Barbecuing’s gendered history has left a lasting cultural imprint. Today, women grill as often as men, but the stereotype of the “dad at the barbecue” persists. Cooking indoors, particularly daily meals, is still often feminised, while outdoor grilling is depicted as a performance, a leisure activity, or even a hobby for men.

The truth is, there’s nothing inherently masculine about fire, smoke, or flipping burgers. The entire association was crafted by mid-century advertisers to sell grills, charcoal, and cuts of meat. But their campaign worked so well that more than 70 years later, the “grill master” image still smoulders in our collective imagination.

The next time you’re at a backyard cookout and someone hands the tongs to “dad,” remember: it’s not ancient tradition at play. It’s the lingering echo of a sales pitch, cooked up in the golden age of advertising, still sizzling on the coals.